Popular Posts

Read anything in the news about the Federal Reserve these says and you might run into the term “quantitative easing.”

Besides being hard to spell, the whole concept is a bit hard to understand at first. In the simplest terms, quantitative easing (QE) is nothing more than lowering the cost of money.

The goal of the Fed and other central banks around the world is to support the economy in times of stress. If economic growth slows or contracts, that can mean job losses.

Those job losses then can result in less spending by consumers, defaulted loans on cars and homes and, in turn, these things slow the economy even more.

A painful spiral ensues, one which central banks exist to fight.

Normally, they do this work through the interest rate. Since recessions are difficult to forecast, the banks try instead to estimate the chances of slowdown in the months to come.

If conditions seem to be weakening, they can target a lower interest rate by doing normal central bank things, such as announcing a move to lower bank lending rates by lowering the rate central banks charge to get money.

If the Fed is successful the market responds to the prospect of lower rates and companies are slower to lay off workers or cancel expansion plans. They know they can secure cheap loans if necessary, and that fact tends to promote growth.

Conversely, of course, if growth is too hot and inflation is building, banks can raise rates to slow things down, but that’s another column.

So what is quantitative easing?

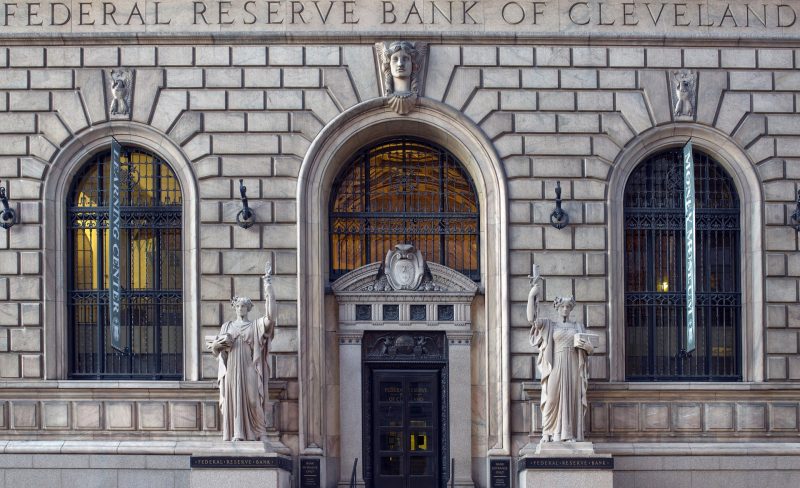

Well, in 2007, the Federal Reserve saw a much larger problem ahead. It wasn’t just that companies were laying off workers. The whole financial system was about to seize up.

The problem was a huge number of questionable home loans that had been repackaged as a kind of bond for investors. The housing crisis was imminent.

Fearing a collapse of many large banks, the Fed decided that ordinary interest rate mechanics would be too little, too slow to face the looming risk.

Instead, they bank choose to simply buy government bonds in very large amounts, eventually several trillion dollars’ worth.

Those bonds were owned by the banks. By exchanging cash for the bonds, the Federal Reserve made it abundantly clear to the banking system, and everyone else in the economy, that the banks would not be allowed to collapse overnight.

In other countries, notably Japan, this was done by purchasing stocks as well. The flood of money might or might not be immediately lent out by banks, but there was no reason for depositors or the markets to panic and try to remove their cash — the banks had plenty of it.

While complicated and hotly debated still, it seems clear in retrospect that the Fed’s actions helped to stave off a much worse outcome, and possibly even forestalled a repeat of the Great Depression.

Now, more than a decade later, banks around the globe are again considering doing more quantitative easing, this time to avoid deflation, or falling prices. It’s not quite the emergency of years before, but the tools are similar.

MarketRiders, Inc. is a registered investment adviser. Information presented is for educational purposes only and does not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any specific securities, investments, or investment strategies. Investments involve risk and, unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.